Users Who Spiked

THE LONE AND LEVEL SANDS || CHAPTER 7

Private Notes

Private Notes

Notes

He woke a mile away from the toppled mountain beneath a cedar tree. The dust was still settling, and the animals were coming out of their hiding places to seek shelter from the debris and rain. He had no idea how long he had been unconscious, and he was exhausted. It was night, the rain still came down, and the moon was a glowing crescent behind the clouds. He was sore, his head pounded with searing pain, his throat was dry and raw, his stomach was empty, and the world was silent.

Krastos was buried beneath the mountain, and it took Tarlos several hours of digging and lifting boulders with his Power to find his brother's mangled body. He pulled him from the rubble. Krastos's chest was flat, his limbs shattered, his clothes torn beneath his flattened armor. With his mind, Tarlos lifted him away from the wreckage, and he did not look for any sign of the defeated Bawa.

It was only when Tarlos landed Krastos at a safe long distance from any view of the crumbled mountain, while they were both under shade and hidden from the sun, that Tarlos allowed himself to cry. He touched Krastos, ran his hand over his shattered arms and legs, felt the flatness of his torso, cleared a stray tooth away that had embedded into his cheek.

Krastos's eyes were open, and Tarlos went to close them, but he paused. He took a moment to look into the dead eyes, and he saw that there was nothing behind them. There was no light, no peace, no discomfort either. This body did not know that it was once a living person. Krastos was gone, and that was that. Everything Krastos had ever done was now rendered meaningless.

Something was beneath Krastos's shirt, and Tarlos pulled it out. It was the talisman that Lakaeus had given him. By the time Tarlos finished crying, the moon had set and the sun shone through the forest canopy.

The horses were gone, either run away or buried beneath the mountain with countless other animals. Tarlos did not have the mental energy to levitate Krastos all the way back to Kesh, and he could not lift him. Using some fallen branches and Krastos's torn shirt, Tarlos lashed together a sledge and placed his brother's body on it. Pulling him across the desert was not ideal, but he had no other choice. He would not leave Krastos in the Cedar Forest and then send soldiers to fetch him. They had come to fight Bawa together, and they were leaving together.

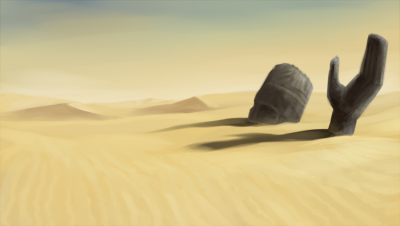

Hours passed, and when the forest ended and the desert began, Tarlos's steps became slow and labored. He struggled to pull the sledge with Krastos's huge broken body. Only a few miles away from the forest, he had to set it down and take a break. He collapsed on the ground, faint from thirst and the heat and the brightness of the sun. He cried some more, and then he fell asleep.

Feathers flutter around him, the sound of a breeze through dried corn husks. It is dark, but Tarlos can see shadows of grey against a backdrop of black.

One of the shadows approaches him, and at first he thinks it is some kind of mutant bird, hunched over and walking on two tall legs. But as it comes near, he sees that the figure is a tall man, and the man is wearing a cloak of black feathers.

"The mountain," Tarlos says in Krastos's voice (is he Krastos?). "I didn't want to kill it."

"That didn't stop you from killing it, though, did it?" the man replies. His voice is dry and hollow like wind blowing through the discarded dead skin of a snake. His eyes are grey and blank.

The man bends beside Tarlos and scoops a handful of clay from the ground. He welds his eyes to Tarlos's as he brings the clay to his mouth and takes a bite. He chews, and his saliva mixes with the clay and spills from his lips in a red-brown liquid and drips from his chin. Tarlos backs away, disgusted.

He collides with another person, and he turns to see a woman dressed in feathers, munching on clay. Her teeth are black, and her eyes see no light.

Tarlos cries out and runs, but all around him are people wearing feathers and eating clay, and they all dwell in darkness.

"I didn't want to kill him!" he shouts into the abyss, as men and women turn to see him, clay falling from their lips and between their fingers as they grasp at the cold ground. "I didn't want to kill him! I didn't want to kill him!"

But then he realizes that he is not the one shouting this. He hears it, and the voice is far away. He runs to it because the voice is familiar. And there he is (there is Tarlos—he is Krastos—he sees himself through Krastos's eyes) kneeling beside a sarcophagus. The other Tarlos cries and pounds the heavy coffin, which is carved and painted to look like a man. Like him.

Krastos.

"I didn't want to kill him," Tarlos says over and over and over.

Tarlos/Krastos reaches a shaky hand toward himself/his twin and touches his shoulder. The other Tarlos turns at his touch, and his eyes are the same dark and empty ones that belong to the people who eat clay and wear feathers.

Tarlos/Krastos screams, and he runs. The clay-eaters follow him, shambling along at a miserable pace, but they somehow keep up with him.

"Who are you?" he cries out to them.

Behind him, a clammy dead hand grabs his neck and plunges the other hand into his beard to hold his chin. A hollow wisp of a voice whispers in his ear, "We forget. We forget, and no one remembers."

Tarlos woke calmly from his nightmare, thinking it odd that he was not thrashing or screaming or sweating. His eyes stung, and they were puffy with sleep and tears, and he rubbed them until they could focus on the stars and moon above him.

"Tarlos," spoke a woman's voice.

He turned to the voice, and there sat a blazing fire that had not been there a moment ago. Sitting on the other side of the fire was a woman dressed in all white. Her hair was also white, and it floated around her head as if she were underwater. Her skin was like porcelain. The only part of her that was not white was her icy blue eyes.

"Who are you?" Tarlos asked. His voice was cracked, weak from thirst and sobs.

"I am Hashri," the woman answered, and Tarlos straightened at the name.

Hashri was the goddess of death, she who watched over all the souls who crossed over to the Nether. Seeing a living, breathing goddess sitting before him did not shake him, and his heart did not speed its beating even a single degree. Tarlos was fed up with his life, ready for anything to happen. If a goddess was here to take him down the Styx, then so be it. He had no desire to live after what had just happened.

"Why are you here?" he asked.

"I thought you might want to know the state of your brother's soul," she said. Her voice echoed in Tarlos's head, and the sound made him want to weep for everything that had ever passed away.

"He's dead. Please leave me alone." Tarlos turned from her and made to lay down beside the sledge and Krastos. "I don't want anything to do with the gods."

An unseen force kept Tarlos from facing away from the goddess, and his eyes were glued to her flawless face.

"Krastos lived a wonderful life," she said. Her voice was even, calm, and reassuring, like the sea after a storm, but it did not make Tarlos feel better. "He brought honor to his name and to his memory, and he overcame the burden that was his father's legacy."

This last bit confused Tarlos, and he brushed it aside for the moment, reminded of something that he had wondered to himself earlier. "Where was Moleg?" he asked Hashri. "He wasn't there to protect my mother, and he wasn't there to protect Krastos. His own son. Where was Moleg when my brother needed him most?"

"My brother Moleg has no mortal children," Hashri said. "Perhaps you should inquire about this when you return home. And you must return quickly, as forces beyond you conspire for the throne on which you will soon sit. Be at peace knowing that Krastos does not suffer in the Nether. Farewell, Tarlos, son of Lakaeus."

In less time than it takes to blink, the fire was gone and Hashri no longer sat before Tarlos. He was alone in the dark, alone with the stars and the song of the crickets, and a dead brother.

When he reached Kesh three days later, Tarlos was dehydrated and sunburnt and still in shock. He wondered if he had blinked even once since he left the Cedar Forest. The skyscraping walls of Kesh stood before him, a red dot in a yellow desert against a backdrop of stars. He pressed on, dragging Krastos behind him. The sledge was coming apart as the shirt that held it together frayed and tore.

Tarlos stopped at the huge gates and dropped the sledge to the ground. It landed in a puff of dirt, and Tarlos collapsed into a sitting position beside it. He looked at Krastos, or what was once Krastos, and felt his bottom lip quiver.

"Made it," he said, and then he fell backwards and slept in the dirt.

He woke to a spear pointing at his face and three armed guards standing above him. He shielded his eyes from the sun that was rising over the city walls.

"State your business," one of the guards said through his helmet. The spear inched closer to Tarlos's face.

He sat up, slowly, and coughed. "I'm here to bury my brother."

The three guards looked at Tarlos for several moments before one of them gasped.

"Prince Tarlos!" he shouted, and dropped to one knee. The others followed his example, and the spears fell away from Tarlos.

One of the guards looked to the sledge, and his eyes grew wide. "That's not..."

Tarlos nodded. "If you wouldn't mind, I'd like you three to take Krastos to the temple to have him prepared for burial. I'm just going to sit here for a minute longer."

The guards bowed, and a stretcher was brought from the other side of the gates where the guards were stationed. They carried away the body of Krastos, and Tarlos watched them leave through the city. Dozens of heads turned and watched the small precession, and no one recognized their dead prince.

Tarlos put his head in his hands and breathed. The day was hot, the sand was hotter, his skin was burnt, and his heart was frozen. He apologized to the ground with his eyes closed, whispering to himself and to the gods and to his brother. He did not know whether or not they could hear him, but he did not care either way. He did not care about anything anymore.

Tarlos had Krastos's body cleaned, embalmed, and wrapped in linens. Nekhte himself made a solid gold sarcophagus and formed it into Krastos's image. The priestesses took care when placing Krastos's body into the coffin. Shala, a small and young priestess, held back her tears as she helped. Before the sarcophagus was shut and sealed, Tarlos made sure to lay the talisman Lakaeus had given him on his chest, above his crossed arms.

All of Kesh was required to come to the prince's funeral, and all did come. They gathered at the Tomb of Kings, twelve miles south of Kesh, and Krastos was carried by a team of stallions. There they watched and listened in reverent silence as the High Priestess conducted the burial.

The High Priestess held her palms to her face and lifted her chin to the sky. She spoke in a loud but respectful voice.

"Hashri, everything that is undesirable of Krastos has been carried away for you." She picked up a vase of water and lightly poured it over the sarcophagus.

"Any evil which was spoken in his name, Ilshu has received and cast it into the Styx.

"The fluid of life shall not be destroyed in you, and you shall not be destroyed in it. Let him that departs depart with his soul. Hefmut departs with his soul. Moleg departs with his soul. Sekhmet departs with his soul. Sep departs with his soul. Ninety-nine gods and ninety-nine more depart with his soul.

"Krastos, the arm of your soul is before you and behind you.

"Krastos, the leg of your soul is before you and behind you.

"Hashri, I give unto you the offering of Hefmut, that your belly may be filled with the flesh and your body surrounded by the odor."

A small white sheep was brought to the High Priestess, led on a rope by two young priestesses. The High Priestess removed a long knife from her belt, held it to the sky, then slit the sheep's throat. Blood poured over the ground as the sheep bleated and twitched its hind leg.

"This libation is for you, Hashri. This libation is for you, Krastos."

A priestess brought her four sticks of incense, and she lit them and waved them around the sarcophagus.

"As Hefmut advances, and as Moleg advances, and as Sekhmet advances, and at Sep advances, so shall Ilshu advance with your soul.

"Hail Ilshu, king of the dead. Hail Hashri, queen of the dead. Hail to the gods of death who live forever, who were born of heaven, conceived of Shar and Moresh. Into your hands we commend the soul of Krastos."

Soldiers placed Krastos in his tomb. Treasures were placed around him, and fresh paintings on the walls depicted his wonderful life—from his miraculous birth and childhood, to his many feats of strength and service, to the battle with the manticore, and finally his selfless sacrifice in the fight against Bawa.

The door to Krastos's tomb was sealed shut, never to be entered again.

The sermon was word-for-word the same as every funeral since the beginning of their religion. Tarlos expected no different. But after hearing his brother receive the same funeral as his mother eight years before, with only their names switched out, Tarlos felt a small pit of anger in his belly. Why could they not at least take a moment and say something about Krastos's life?

Tarlos stood at the entrance to the tomb, and he ran his hand over the glyphs that represented Krastos's name, carved into the stone above the door. Behind him, the people of Kesh left the Tomb of Kings and made their way back to the city. Tears stung at Tarlos's eyes as not one person stayed even a few minutes after Krastos was shut up in darkness forever.

"And just like that," Tarlos said to the door, "you're gone."

The royal concubines lived together in a mansion next to the palace grounds. Like everything else in Kesh, it was built from cedar wood and did not stand apart in appearance from the surrounding houses and structures. The morning light shone through the windows and doors of the mansion, casting slats of light onto the grounds and gardens in front of it. There was no movement other than laundry hanging out to dry, flapping in the breeze. The concubines liked to sleep late, and Tarlos did not expect any of them to be awake at this hour. Kamhat would be in there, in her private room, confined to her bed with shattered hips. The slaves working in the gardens turned their heads and bowed as Tarlos walked past them into the mansion, and it was not their place to say anything to him.

The heavy cedar doors opened silently, and there was not a single concubine to be seen. Slaves walked around the place cleaning and fluffing pillows and filling jugs with water and wine. More slaves could be heard in the kitchen preparing a midday meal. A few of them looked his way as he walked through the main room and up the stairs to the topmost floor, but none spoke a word to him. As much as he respected the slaves, he was in no mood to speak to them as equals as he often did, and he was grateful that none gave him the opportunity to scream at them.

Kamhat's room was at the end of the hall, and Tarlos made his way to it with silent and sure steps. Suddenly he was aware of how dry his eyes and throat were, and he had to stop to compose himself before going in.

She was there in her bed, just as Tarlos had imagined. Her covers were unwrinkled over her frail body, and it seemed that she had not moved since the incident. She was thin and sickly, pale with sunken cheeks. She opened her eyes as soon as Tarlos entered the room.

"Prince," she said. Her usual sensual voice was now raspy and weak, and Tarlos almost felt sorry for her as she lay broken and useless and forgotten in this room. "I am sorry."

Tarlos stared at her, running his eyes up and down the lump of her body that lay beneath the blanket. Kamhat played with her hands as Tarlos said nothing for a few minutes.

Finally, he exhaled through his nose in an aggressive sigh and said, "Why is it that you, a whore and a harlot, get to live after what you've been through—and yet my brother, who never did a single wrong deed in his life, is now dead and forgotten to the world? Tell me."

Tears welled up in her eyes, and her mouth shook. "I...I..."

"Tell me what happened that night," Tarlos said. "The truth. I know it wasn't him."

It was plain to see that Kamhat was seriously injured, and Tarlos did not think she would ever walk again. Part of him felt sorry for her, but the other part was waiting to hear what she had to say before he extended any sympathy.

She shook her head, eyes still wet. "I don't know what you—"

"Just tell me," he spat. "I have had a terrible decan. I watched my brother die, I dragged him across the desert for three days. I stood there and watched as everyone in Kesh left as soon as the sermon was over at his funeral, and no one stayed to pay their respects. I am livid, and I'm in no mood to play games with you."

"I..." Kamhat closed her eyes, and a tear fell down her cheek. She turned away from him. "I'm sorry, prince. I don't know what you want me to say."

Tarlos lifted her with his mind, and she hovered six feet above his head. She screamed in pain as her legs dangled beneath her, and Tarlos saw the bandages and plaster around her waist and thighs. She cried out and shouted, but he did not understand anything she said through his own rage.

"You're responsible for this!" he yelled over her cries. "This is your fault! He'd still be alive if it weren't for you! And I hope you rot in the House of Dust for all eternity!"

She screeched, "Put me down and I'll tell you!"

Tarlos dropped her on the bed, and she took several seconds to cry, wipe her eyes, and adjust her position. When she was finished, she could not make eye contact with Tarlos.

Tears streamed down her thin and sunken face, and she said between sobs, "Krastos had nothing to do with it. It was the guards who broke me. With hammers. They told me they would kill me if I said anything, and they told me to say that it was Krastos who did it. Do you understand, Tarlos? They were going to kill me!"

"Why?" Tarlos asked. His blood boiled. "The guards wouldn't do that on their own accord. Who gave them the order?"

"Please, prince..."

Tarlos brought a heavy fist down on her waist and pummeled her twice. She screamed again. "Tell me," he said.

"I don't know!" she cried. "I would tell you! But I just don't know. Who would want to frame Krastos? I can't think of anyone, and I've thought about it a lot." She breathed in, and her breath shook, and she wiped her eyes and bit her lips. "They would have killed me. I am so sorry, Tarlos. So sorry..."

Tarlos could think of nothing to say, and he left her there. He heard her continue to cry as he left the mansion and made his way to the palace.

The palace was silent, and almost all inside were asleep. It was a short and easy walk from a side door in the courtyard up the stairs to the king's apartment. The guards nodded to him, and he opened the door slowly. It creaked low and quiet on the hinges. The door opened just wide enough for him to slip through, and it closed behind him. The apartment was dark, as it always was, and not even the sun could be seen through the thick black curtains. The king's body slave slept in a small private room just a few feet away, and Tarlos locked it from the outside, then tugged on the door to make sure it would not open.

His father slept in his bed, his small malnourished chest rising and falling only a few inches. The sick and raspy breathing of the king made Tarlos ill. He watched his father sleep for a few minutes, letting it become real that this would be the last time he saw his father alive if things happened how he imagined.

With a snort, the king yawned and rolled over in his sleep, and the blanket covering him slipped off and revealed his thin legs. Tarlos used his Power to pull the blanket off entirely, and the king shivered. In Kesh, it was hot no matter the time of day or night, but Lakaeus had been having chills for the last several months. This was a sign that his death was near. And his death was nearer than he knew.

Lakaeus opened his eyes and searched with a wandering arm for his blanket, and Tarlos stepped forward. The cedar floor creaked beneath his feet, and Lakaeus stopped moving.

"Someone there?" he asked. His voice was weak and cracking with sleep and sickness. "Abu? Is that you?"

Tarlos whispered, "It's me, Father."

Lakaeus sat up fully, struggling with his skinny weak arms to prop himself up against his headboard. "Tarlos! Gods, boy, where have you been? I have so many things to say to you and I don't know where to start..."

"I guess you know by now that Krastos is dead." Tarlos took another step forward. His eyes were adjusting to the dark room, and he could see his father's eyes clearly. Was the king only tired, or did Tarlos see worry in those grey eyes?

The king cleared his throat. "Yes. Although they didn't tell me how it happened. How did it happen?"

"Bawa killed him. Actually, Krastos sacrificed himself to save my life." Another step toward his father and the king leaned away from his son. "I need to ask you something, and you need to answer truthfully."

Lakaeus licked his cracked lips and nodded. "Go ahead."

"Was Moleg truly Krastos's father?" He had to whisper the question. He feared that if he used his voice he might cry.

Lakaeus swallowed and ran his fingers through his hair and his scraggly beard. He shook his head, looking away from Tarlos, and he said in a soft voice, "No. Moleg was not his father."

"Then who was his father? Because it surely wasn't you."

The king looked at Tarlos, and Tarlos saw the worry in his eyes for sure this time. Alongside the worry was fury, and the king lowered his head in anger and said, "Ablis."

Tarlos stumbled back a step, not believing it at first. But after a moment's thought, it all made sense.

"Mother's life was the price for a son," Tarlos said, finally understanding. "That's why Bawa killed her—because she made a deal with Ablis. You were responsible for the manticore. You wanted Krastos dead!"

"The manticore should have killed him, even being the demigod that he was," the king spat, using his thin shaking arms to straighten himself against the headboard to better meet Tarlos's gaze straight on. "I know you helped him kill it, but there was nothing I could do about it. So something else had to be done."

"You almost killed Kamhat just to have an excuse to kill Krastos." Tarlos took two steps forward, fire burning in his veins and thunder raging in his heart. "You blame him for Mother's death, don't you?"

"Ninsun would still be alive if that abomination were never born!" Lakaeus's chest rose and fell tremendously, and he put a hand on his chest and coughed as his heartbeat grew too quick.

They stayed in silence for some time. Tarlos stared at the king, and the king stared at his son. Tarlos knew what he had to do, and he thought a part of the king knew it as well.

Tarlos said, "I'm going to kill you now."

The king sneered. "Fine. Send me to Paradise. I deserve it after the long life I've lived."

"You think you will go to Paradise when the House of Dust waits for murderous tyrants like you?" Tarlos scoffed. "You will rot in Hell for all time. And when you are dead, I will blot your name from every record, and I will make it illegal to even utter your name, and soon there will come a day when Lakaeus son of Hestos might as well have never existed in the first place. Then you will truly be dead."

Lakaeus sniffed and whispered, "Then I shall wait for you in Hell, my son."

Tarlos shook his head. "No. I'm going to the Ageless Country, and I will learn the secret to immortality. I will be the last king of Kesh, and no more men like you will ever sit on the throne again."

The king raised his head, and his shaking arms gave out, and he slumped onto his bed.

Tarlos asked, "Will you try to defend yourself?"

Lakaeus sighed and shook his head. "It wouldn't do any good. I'm dying anyway. And the world must have a Holder of Space, so I cannot kill you. Do what you will."

Tarlos reached into his father's lungs with his mind and pulled out the air. He closed the king's throat, and the king gurgled and choked for a few seconds, and then he fell over onto his bed with a blue face.

Tarlos did not give his father the honor of being buried. Lakaeus's body was burned, and his ashes thrown to the wind.

The High Priestess performed the coronation after Lakaeus was disposed of, and Tarlos became the new king of Kesh. The crown was cold and a bit too small. It hurt to wear it, so he hardly ever did.

Sleep did not come to Tarlos for many nights, not even with the warm comfort of Katla beside him.

"Just close your eyes and lay down, and sleep will come," the queen would say to him.

"Why should I sleep when my brother will never wake again?" Tarlos replied one night.

"He's alive in your heart and in your memories, Tarlos."

But Tarlos just rolled away from her and stared at the wall every night until the sun rose.

In the rare moments when his eyes did close and his mind slipped into something close to sleep, nightmares plagued him. Rustling feathers, clammy hands, mouths full of clay, weeping, voices like dry grass...

No, Tarlos would not die. He spoke the truth to his father. As he looked into the polished copper plate at his reflection and shaved his beard, he knew a truth. Immortality was the only solution to his misery.